Horner's flowers

Some eight years ago when we began our way of craftsmanship, horn was the very first animal hard tissue material we started to explore.

Horn is a material that seldom survive in the ground therefore archaeological examples of hornworking are few and far between. The most ancient object found we know of is dated to c. 950 to 1050 [1], but later in medieval era and then also in early modern era and all through to the early 19th century the specialists in hornworking are often mentioned in historical documents as horners. Different kinds of produce can be ascribed to horners, indeed it seems to have been an industry with many branches and expressions, but the horners proper engaged in making of translucent horn sheets, for horn-books, lanterns, windows and such. That's why the demise of this profession coincides with the discovery of new sheet-glass making technologies at the end of 18th century [2].

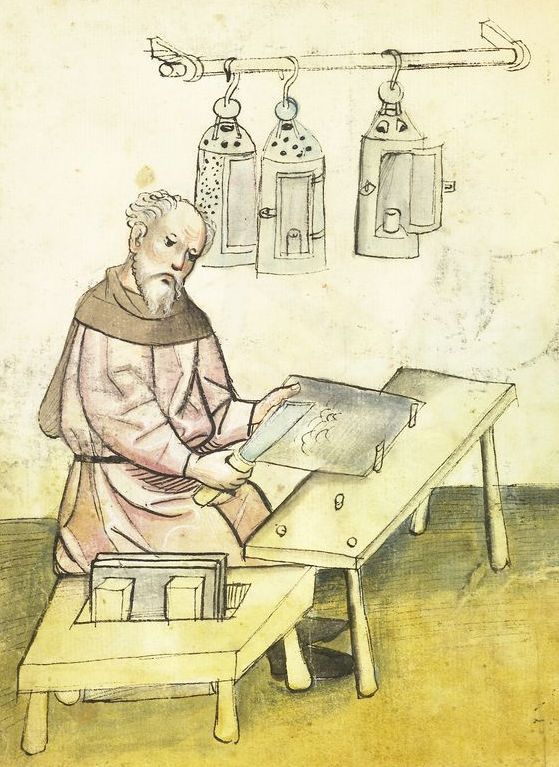

Fritz Hornrichter at work. An image from the famous

Die Hausbücher der Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen, beginning of the 15th c.

Fritz Hornrichter at work. An image from the famous

Die Hausbücher der Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen, beginning of the 15th c.

What refers to medieval horners and their tricks of the trade, many legends circulate nowadays. One of such legends we debunked only recently.

It is sometimes mentioned that back in ''those days'' horners mastered a technique that allowed to ''weld'' together several plates of horn so that a larger one-piece plate could be achieved [3]. This technique, as so many things, has now, of course, been lost in the mist of past together with the treasures of the Templars.

Well, everybody who have had some more or less serious experience in working with this wonderful material will know that it doesn't give any promise to be weldable, no matter what tricks you come up with. But that is not to say that horn sheets were not indeed joined together - they were, usually and quite often at that - only not by any kind of ''welding'', ''soldering'' and such.

Look at this one picture below and, Fortune smiling, you will know the truth in no time! Notice the division of the window of this lantern? Such divisions can be seen in countless depictions of medieval lanterns, so much so that one can assume them to be a typical feature. All the secret is hidden behind those lovely pewter flowers. Of course, one can connect two horn plates also without these ornaments, sometimes even a wooden crossbar has been used instead, but they make the whole lantern so much more brighter in a way!

With these observations in the pocket, we have started to sprout our own horner's flowers for use in our next projects.

[1] Kinmonth C. Irish horn spoons: their design history and social significance // Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol. 118

[3]

e.g.

Lord Mikal Isernfocar, called Ironhawk Working with Horn and Skeletal Materials booklet, chapter ''Hot work techniques''

Not about bone china yet

...But in medieval Europe ceramics often met bone in the shape of potter's combs and similar tools for shaping and decorating clay vessels.

Potter at work. Note the potter's comb in her right arm. Depiction on the mid- 15th century German playing card.

Potter at work. Note the potter's comb in her right arm. Depiction on the mid- 15th century German playing card.

By the contemporary depictions alone it is not

possible to distinguish the material such potter's tools are made of;

also wood could have been used as well.

Archaeology provides us with examples of potter's tools made of animal skeletal materials. Here we present you two of the most famous of these - one from Inwroclaw (Poland) and the other from Viljandi (Estonia) .

The Inwroclaw potter's comb [1] is of simple design that very much resemble the one depicted above. The function of it thus can be clearly understood.

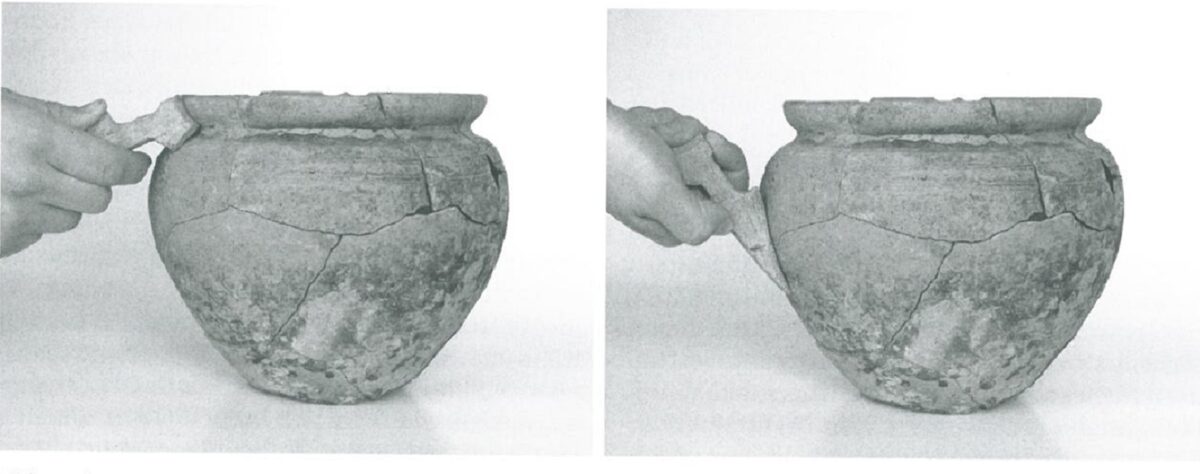

The Viljandi find [2] asks for further explications. If it wasn't found in a context of a pottery kiln then certainly this object would have joined ranks of finds with unidentified/unclear function. But look, how nicely it snuggles against the curved surfaces of pots found at the same digs:

Images from ''Handwerk in den Kleinstädten Estlands im

13. bis 17. Jahrhundert im Spiegel der Archäologischen Ausgrabungen

'' and ''Pihkva Pottepad Viljandis ja Tartus 13. Sajandil''.

Images from ''Handwerk in den Kleinstädten Estlands im

13. bis 17. Jahrhundert im Spiegel der Archäologischen Ausgrabungen

'' and ''Pihkva Pottepad Viljandis ja Tartus 13. Sajandil''.

Below are image of our replicas of these two finds. See more here.

[1] - Pawłowska K. The remains of a late medieval workshop in Inowroclaw (Kuyavia, Poland): horncores, antlers and bones //Written in Bones. Studies on technological and social contexts of past faunal skeletal remains.

[2] - Pärn A., Rossow E. Handwerk in den Kleinstädten Estlands im 13. bis 17. Jahrhundert im Spiegel der Archäologischen Ausgrabungen // Lübecker Kolloquium zur Stadtarchäologie im Hanseraum V: Das Handwerk.

Tvauri A. Pihkva Pottepad Viljandis ja Tartus 13. Sajandil //Eesti Arheoloogia Ajakiri, 2000. (4)

Russow E., Haak A. An outline of pottery production and consumption in medieval and early modern Estonia // 2nd MEETING OF BALTIC AND NORTH ATLANTIC POTTERY RESEARCH GROUP Tallinn, 12th and 13th April 2018 Programme – Abstracts – Outlines

Gesso for the unversed

The playful deer

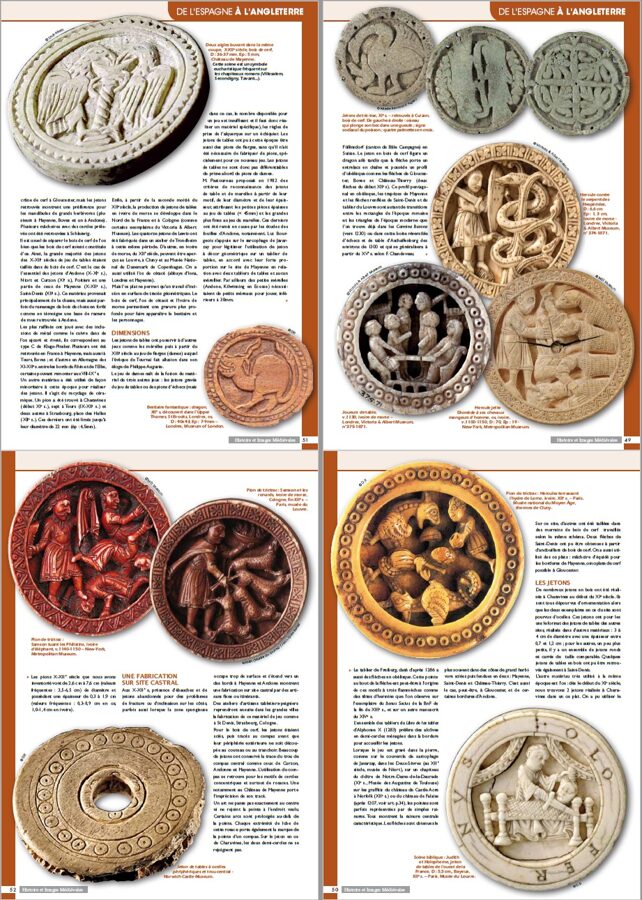

European archaeology testifies a proliferation of carved gaming counters for tabula type of games during the 10th to 12th centuries. The most famous of such finds is a complete set of counters from Gloucester, but there are countless more separate finds as from the South, so from the North.

Some examples of carved gaming counters from France, Germany and British isles in the popular magazine ''Histoire et Images

Médiévales

'' No. 28 (2012).

Some examples of carved gaming counters from France, Germany and British isles in the popular magazine ''Histoire et Images

Médiévales

'' No. 28 (2012).

One lovely, but lesser known example comes from Daugmale hillfort in Latvia. It tells a story of an artifact that was created for gaming, but at some point continued its career as a pendant in this bustling trading post at the river Daugava.

See few more pictures of our playful deer here.

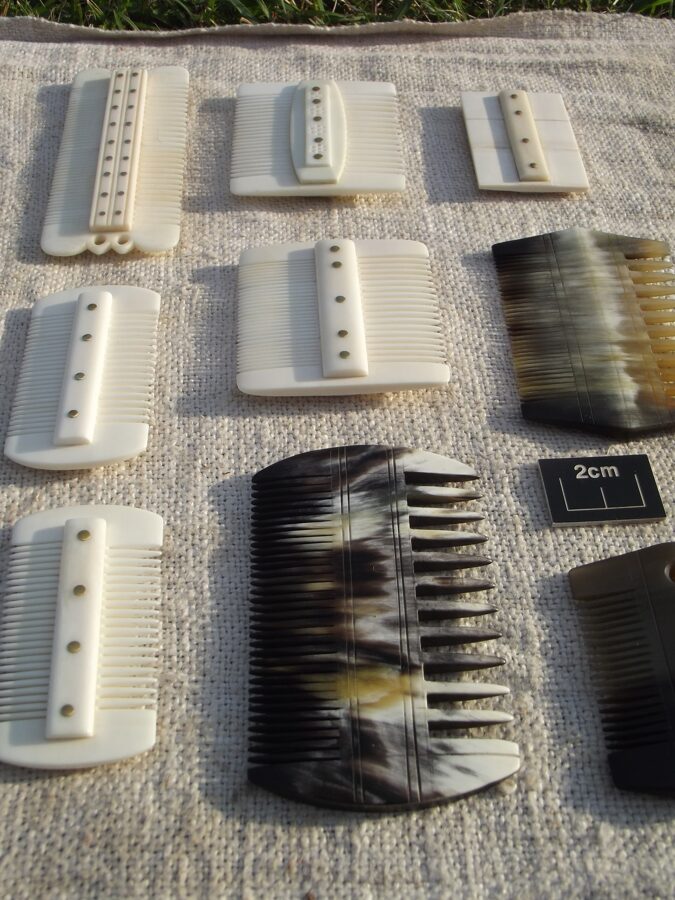

Simple and beautiful

This comb is lovely example of the simplest type of the 13th/14th century bone combs - combs with rectangular end plates. It is a replica of find from the old town of Riga, but this type of combs have been widely used all throughout the Europe. See some more pictures here.

Different sorts of dice

Cubic dice, longdice, stickdice, teetotum, astragali. There is always too much or too little to say about dice. This time we put the following two works on the menu for you to suit yourselves according to appetite:

Küchelmann

H.C. Why 7? Rules and exceptions in the numbering of dice

Holmgren R. ''Money on the hoof'' The astragalus bone - religion, gaming and primitive money

The mysterious viking age awls

Nowadays archaeologists identify this kind of artifacts as awls and there can be not much doubt that they could fill this role of a simple tool quite fine. However, a shadow of doubt over this recognition is cast by the inexplainable presence of often lavish decoration on their bone or antler handles. The quality of the carvings clearly exclude simple doodling done by an idle craftsman. Antler handle alone would make it quite an exceptional awl, but the ornamentation that the largest part of these objects manifest seems to quietly whisper that we yet do not know enough about them.

It seems that for the most part awls, as simple and humble tools that they are, have had nice wooden handles and thus after centuries in soil all that is left of them are not impressive looking iron rods [1]. Whereas, look at some of these here: https://sagy.vikingove.cz/en/early-medieval-awls/ (may the authors of sagy vikingove live long and prosperous for gathering images of so many of these artifacts in one place!). And those are not at all all of them, in the archaeology of Latvia alone we have many others. But what might they really be?

[1] E.g. Mould Q., Carlisle I., Cameron E. Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Leather and Leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York, figs. 1574 - 1575

Our ''awl'' is based on the find from Āraiši lake dwelling, also depicted on the website mentioned above.

Black berries

Different kinds of stains are used by modern bone carvers to highlight the relief or decorations of their carvings or to tint the item so as to ''age'' it. The most common recipes for such stains consist of one of these unsophisticated materiae - tea, coffee, soy sauce, tumeric, potassium permanganate...

But now, as we approach the end of the last month of the autumn - the season of fruits and berries- it is time to prepare ourselves better for the next autumn by poking our nose in ''the scriptures'' to see what hints to authentic medieval stains we might encounter there. To make our wagon in the winter and our sleigh in summer, as saying goes.

First of all we have to say that even without any appearances in texts or other sources of history, an endless variety of brews made from common natural materials would be more appropriate for the use in making of replicas of medieval objects than above stated ''devilish'' liquids. So there is wide open field for experiments before us.

And now to our berries! It is common buckthorn (

Rhamnus cathartica

). You will encounter the necessary hints if you search for this amazing an unparalleled work entitled Archeologie en geschiedenis van een middeleeuwse woonwijk onder de Hopmarkt te Aalst (red. Koen De Groote & Jan Moens, issued in 2018) and open it on page 391. Yes, it could be meant for woodwork, but as it has been used in crossbowmaker's workshop, bone and antler was never far from these berries there (look at this lovely specimen for example).

During the last leg of this autumn we indeed managed to get our hands on a small quantity of common buckthorn berries and the preliminary results of experiments with those are forthcoming. But we also got some other wild fruits that seems to be similarly promising - the berries of black elderberry ( Sambucus nigra ). These we even took decent photos of (as one below).

Bone and horn combs

Where can you see professional combmakers at work nowadays? In obscure videos from the 70ies about Switzerland in Spanish. Not in vain it is often said that each new language opens a new world.

Tools looking sweet

https://www.facebook.com/theblackmarketofthewhitebones/posts/

Along different craftsmen also ''common men'' (and women) used to make some simple and useful everyday items from bone by themselves. Few typical examples of this medieval domestic production are bone needles, bone whistles, skates and flutes, and a specific kind of spindle whorls (things that require only a knife to produce).

These last ones are also the heroes of today's story.

Introductory note

As the opening page of this site should be kept as short and to the point as possible, we decided to move some sentences from it here:

Very little of the

knowledge of medieval craftsmen have survived in written form, a lot

more can be learned through objects uncovered by archaeologists. To

''distill'' the information out of these objects requires a fair amount

of understanding and attention to detail. Through finely tuned intuition

and observation, some things indeed can be learned straight at the

writing desk. But the Royal Highway through the realm of these strange

materials and their working is, we are certain, in the work itself. Only

when one has worked with these materials, using similar tools to those

used by medieval professionals, one can slowly gain understanding, and

insight, and fine-tune one's intuition so that each archaeological find

''speaks'' under one's gaze.